Vigorous and volatile like his art, THEO PANAYIDES meets an artist who, although a long way from his hippy revolutionary days in London, has never worn a watch or a tie

Kikos Lanitis sits, dressed in black, surrounded by his paintings. All the art on the walls is his own, here a recent political work with words like ‘Crisis’ and ‘Measures’ scrawled collage-like over a portrait of a young girl, there a striking rendition of an old village wedding, based on a photo. The photo amused him, he explains, because not a single person in it was smiling (at the time, smiling for no reason – as in a photo – was viewed as a sign of simple-mindedness), and also perhaps because his own relationship with weddings has been rather erratic. He has three sons by three different marriages, though admittedly he and his third wife Anita – London-raised, and looking considerably younger than her husband – have been together since 1992.

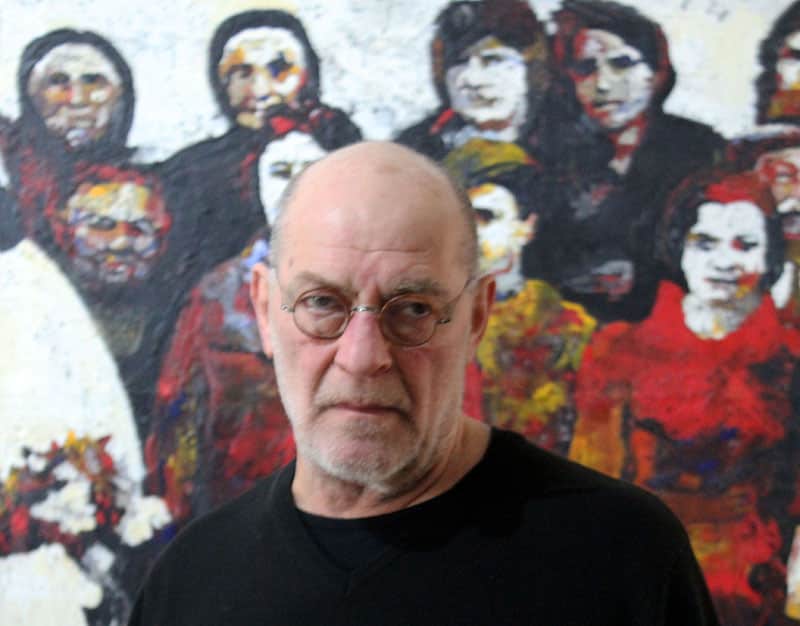

Kikos is tall, with a touch of the bull-like frame he must’ve sported in his youth as a judo champion – he fought for England at junior level, and coached the Cyprus team at the 1980 Moscow Olympics – though also with inevitable wear and tear left by his 70 years on the planet. He has wrinkles under his eyes, and burst blood vessels in his nose; his index finger looks mangled and torn, in what may be an old or a new injury – but his hands are massive, the hands he’s used to daub canvases in the studio and upend opponents in the judo ring, and the eyes are sharp behind round little glasses. Like his art, he gives off a vigorous, volatile energy. His favourite painters are Van Gogh and Caravaggio, he says, and it may or may not be coincidence (I mention the fact, and he laughs indulgently) that one of them went mad and the other was a convicted murderer.

It’s rare to find him here, in this Nicosia townhouse (actually two joined-up flats, taking up an entire floor of a nondescript block in the centre of town). It was even rarer before the economic crisis, when he lived primarily in Athens – but it’s also rare now, when he spends almost all his time in Cyprus at his studio in Pera Pedi, just below Platres. (He’s only in Nicosia for a few days, mostly because he’s just finished an exhibition at Gloria Gallery.) Up in the mountains, he’ll take a two-kilometre walk every day before breakfast, have his coffee beside a little stream, then shut himself off in the studio “and I might not come out till it gets dark, or until 4am, whatever”. It’s much the same in Athens – where he still spends a few months a year – except that he hangs out with other artists and they’ll go down to Kolonaki for an early-morning natter, before it gets busy. “By 10 o’clock we’re done,” he reports briskly, “and we’re all in our studios, working”.

The work is everything; that’s why so many artists fail, because they try to succeed through networking and schmoozing and self-promotion. Art is “for worker bees,” as he puts it, “you have to work all the time, and produce all the time, so you’ll start to learn from the work itself, not from books anymore”. Then again, it’s also a free life. “I’ve never worked a day in my life,” he says paradoxically – meaning office work, clock-watching work. “I’ve never worn a watch, or worn a tie.” His usual spiel, which he likes to recount in interviews, is that he always did badly in school, his only good grades being in Art and PE – so, having concluded that he must be good at those subjects, he became an artist and an athlete, and succeeded in both. “It was only later,” he adds humorously, going for the punchline, “that I discovered that everyone got a 20 in Art, and a 20 in PE!”.

That’s the funny story. The truth is a lot less amusing – though his childhood doesn’t sound abusive per se, just unstable. His parents divorced when Kikos was a baby, leaving him to be raised mostly by his grandparents. His dad had a good job as a company manager, but seems to have been quite an awkward type; his relationship with his in-laws was strained, the one with his son was “perfunctory”. Kikos’ mum moved to England and remarried, playing no part in his life for about 12 years – but then decided that she wanted him there after all, so the ageing grandparents agreed to pass him on. The boy moved from Limassol to London, but never meshed with his new family. At 15, he left home and never went back, working instead as a petrol-pump attendant and restaurant dishwasher – and also becoming part of a hippy commune, joining the 60s revolution with London as its epicentre. “Wherever there was revolution, I was up for it. So, for instance, having a sit-in and blocking traffic at Trafalgar Square, and the cops riding in on horses to break it up – against Vietnam, or whatever. Up for it! It wasn’t like ‘Go to the commune, have lots of sex and that’s it’.”

Kikos was already an athlete, a government grant for his judo training helping him to survive financially (it also helped him to survive in another way: being an athlete, he couldn’t sink as deeply into drink and drugs as most of his fellow rebels) – but he had no thought of becoming an artist, at least professionally. The hippies dabbled in art to make ends meet: the girls in the commune made beads, while Kikos himself gathered cast-off clothes from chic neighbourhoods, dyed them in psychedelic colours then sold them back to trendy shops on Carnaby Street. Slowly, a plan may have formed – he set grocery bags on fire then chucked them in the Thames, the patterns made by the fire before it was extinguished being a form of artistic expression – but his dreams were limited, due to the way he’d grown up. “I was never supposed to come this far in life,” he admits. “No-one had ever set goals for me. Therefore, I had no goals.”

It’s an interesting question, how far – especially for a creative person – a chaotic start is a help or a hindrance. One of Kikos’ many stories is of having mentored (or befriended) Yorgos Lanthimos, the Greek film director who’s up for an Oscar this month for The Favourite. Lanthimos, like him, is another artist with a turbulent early life: his parents divorced, his dad left, then his mother died when Yorgos was in his teens. (Kikos was friends with the family, and helped out while the mum was in hospital.) The result was that Lanthimos, like Kikos, “had nothing to lose” when embarking on his film career (he has also, like Kikos, worked very hard since becoming successful, making five films in less than a decade, as if refusing to take success for granted). “I find, with people who happened not to grow up in a ‘normal’ home, that they’re better at surviving,” he muses. “They’re better at facing life calmly, and more mature at a younger age than the others.”

Doesn’t it create a distance, though? Doesn’t it make for a certain detachment in relationships, having had to harden oneself against life at an early age?

Doesn’t it create a distance, though? Doesn’t it make for a certain detachment in relationships, having had to harden oneself against life at an early age?

He pauses, thinking about it. “I think you have a more correct approach,” he replies. “You don’t do that thing where you fall on the other person and end up smothering them, or getting smothered – or end up having to compromise, or in situations where, at the end of the day, I’m happy on the outside but unhappy, or trapped, on the inside. You’re more free, and more honest. You don’t have this need for social status, which makes you behave so you’ll be accepted by society.”

Isn’t it human nature, though, to want to be loved and accepted?

“Not especially,” replies Kikos. People come and go in this life, he shrugs; often you’ll lose touch with someone and realise you never even said goodbye, because you didn’t know the relationship was ending. The best we can hope for is probably “a closer relationship with some people, for a period of time… So, speaking for myself at least, I don’t get so emotionally attached that I suppress myself in a relationship, or a friendship. It’s ‘Take it or leave it’, as they say.

“And my work is the same way. I don’t think about the viewer, or the commercial aspect – I’m only interested in having a good exhibition. Even if no-one else turned up, I’d take a little stroll through it myself and be happy, because I made a good exhibition… It all comes, basically, from the way you grew up.”

There’s a hardness, to be sure, in Kikos Lanitis. He’s not humourless; asked for the book that changed his life, he cites A Spaniard in the Works, John Lennon’s pun-infested volume of nonsense comedy. (Kikos wrote a weekly current-affairs column in Simerini for many years, trying for the same general tone.) He doesn’t seem cruel, or malicious – but he’s hard, with an athlete’s iron discipline and competitive edge. When he says he’s going to paint, he paints, “it doesn’t matter if 100 people call me saying ‘Come over, we’re having a party’”. He doesn’t look to others for his happiness, nor does he care what people say about his work. I offer an amateurish take on his style – an impression of occluded light, as though light were emanating from behind the painting and being fragmented by the thick, busy surface – but he has little time for analysis: “I believe that, the more an art historian writes about a work, the more it’s a bad work”.

Besides, his style of the past 20 years isn’t all he’s ever done, not by a long shot. He runs through a partial list: abstract art, installations, “arte povera using whatever I happened to find on the street, boilers nailed to the canvas and painted, entire radiators, body performance, painting kids from head to toe – then I wrapped them in a sheet, unwrapped them, and that was the print! – video art, with myself surrounded by glass and getting cut and so on…” He became known in his late 20s (having meanwhile come back to Cyprus, fought in 1974, returned to England and thence to France, where he found his first acclaim), but it wasn’t till his early 40s – his years in Athens – that he really became “indispensable to the society where I lived,” as he puts it, i.e. a leading light of the artistic community, no longer having to hustle for shows and stress about selling his work in the way of an up-and-coming artist.

Besides, his style of the past 20 years isn’t all he’s ever done, not by a long shot. He runs through a partial list: abstract art, installations, “arte povera using whatever I happened to find on the street, boilers nailed to the canvas and painted, entire radiators, body performance, painting kids from head to toe – then I wrapped them in a sheet, unwrapped them, and that was the print! – video art, with myself surrounded by glass and getting cut and so on…” He became known in his late 20s (having meanwhile come back to Cyprus, fought in 1974, returned to England and thence to France, where he found his first acclaim), but it wasn’t till his early 40s – his years in Athens – that he really became “indispensable to the society where I lived,” as he puts it, i.e. a leading light of the artistic community, no longer having to hustle for shows and stress about selling his work in the way of an up-and-coming artist.

And now? That’s another interesting question. Kikos mentions some of the critics and artists who championed his work in Greece – but soon finds himself adding footnotes: this one died last year, that one is now in hospital. He no longer writes his column for Simerini; “You have to know when to stop,” he says ruefully. He’s in no way close to retirement – an artist can’t retire; what would he do without the work? – but growing older has undoubtedly mellowed him. “I try to stay on the outside and be an observer now. I used to be on the inside, but now, at my age, I observe. I notice that I’m no longer – not just me, the same is true of others – I’m no longer so fanatical. I notice I’ve become better at listening now… I used to be more aggressive, more opinionated. Now, even if I’m right, I’ll say something one time – maybe one and a half times – then there’s no point saying it again. Take it or leave it.”

The world has changed too – and, unlike many former hippies, he finds little echo of the 60s in today’s rebellious youth. “What can you change today? Today, there isn’t an enemy… They talk about dropping bombs in Syria – but who’s dropping bombs? They’re all dropping bombs!” It was different in his day, so much simpler to protest against Vietnam and the older generation – and of course there was human contact, unlike today’s social-media-driven protests. “Today they don’t have relationships. I don’t understand it. But the previous generation didn’t understand us, either, so I’m not going to sit here and judge them”. So what’s left of the youthful revolution that shaped his own turbulent youth? Maybe just “the feeling that ‘We failed’,” he replies soberly.

Don’t look to Kikos Lanitis for sentimentality. He started restless, and never really settled down. He’s the enemy of all settled things – whether it’s an office routine or a happy ending, or the reductive satisfaction of a work of art being ‘explained’ by a critic. He’s never worn a watch, as he says, or a tie. He could wake up tomorrow and fly off to Greece, if he wanted; he could work all night, or not work at all – but of course he does work because the work is everything, even (or especially) when it drives him to distraction. He was chatting to a friend who was feeling stressed out once, he says, “and I said to him, ‘You’re stressed out? Can you imagine picking up a brush every morning, and saying to yourself: “With this brush I have to buy a house, I have to send kids through college, I have to do this and that”? And you’re stressed out, working in a bank?’.” It sounds like an exhausting way to live – but of course he doesn’t need my approval, or anyone else’s, to live as he pleases. Take it or leave it.

The post Leading light of art world lives as he pleases appeared first on Cyprus Mail.