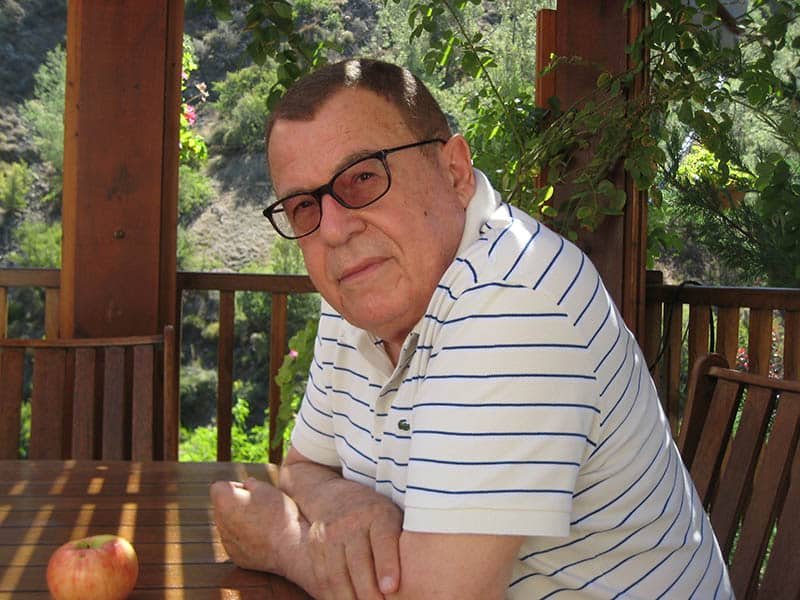

After having brought the village of Kalopanayiotis back to life, one of its leading sons has now been charged with advising the president on an ambitious plan to rejuvenate 115 mountain communities. THEO PANAYIDES meets him

Our interview with Yiannakis Papadouris begins where most other interviews end – at around the one-hour mark, when I switch off my tape recorder. At this point we’re still at his estate outside Kalopanayiotis, wedged in the fertile river valley that runs alongside the village. The estate, on a narrow strip of land, includes a swimming pool and sauna, homes for himself and his daughters Alexa and Emily – though the daughters live in England, and he’s in Dubai or travelling half the month anyway – and a large orchard designed to produce fruit all the year round (there’s an apple on the table beside him, and ‘Renos’ from Hyderabad – not his real name – also cuts me a couple of luscious figs). I switch off the tape recorder, feeling I already have enough to write a profile – but then we get in the car and Yiannakis drives me the eight kilometres to Kalopanayiotis, the village of his birth and the village he’s completely transformed since his return to Cyprus in 2002.

This is where he comes into his own, this rather stocky, 73-year-old man with the penetrating voice and thick glasses. This is where his vision unfolds all around us, with himself as voluble tour guide. Here’s the old coffee shop he bought and restored. Here’s the lift he constructed, as community leader, linking the top and bottom of the steep slope on which the village is built. Here, of course, is Casale Panayiotis, the jewel in his crown and “the lifeblood of the village”, a sprawling 40-room luxury hotel that’s actually a conglomeration of traditional homes in ‘old’ Kalopanayiotis, restored by various architects to give each one a slightly different character.

Yiannakis has bought around 10 properties in total (not counting those in Casale), plus abandoned vineyards; he’s now in the process of building a winery. He has plans – though the picture isn’t totally rosy. He points to a children’s playground as we walk down the narrow main road: “Needless to say, that was my donation,” he notes with a chuckle – and it is indeed needless to say so, simply because no council would’ve spent money on a children’s playground. Like all mountain villages, Kalopanayiotis has an ageing population and very few children live there. The local school closed a decade ago, and – despite the recent transformation – has yet to re-open.

That’s a point to ponder, as we celebrate the turnaround in his village’s fortunes; Kalopanayiotis may be a success story, but it’s both half-complete and atypical. Yiannakis takes me to Loutraki, another refurbished hotel that’s part of Casale and includes an upmarket steak house serving fine imported cuts (the prices, I note from the menu, are too high for locals). The restaurant is doing well, reports the manager – but is there really enough tourism in a small village to sustain all these places? “No,” replies Yiannakis with his usual bluntness. “I sustain them until there is”. Despite an influx of EU funds, this is still a work in progress. Visitor numbers are up, with another 80-90 agrotourism rooms added to Casale’s 40. Local youngsters (such as they are) don’t invariably leave now; young people have been tempted from other villages, even Nicosia – but young families, the true lifeblood of any village, are still very rare. And of course all the other mountain resorts are much, much worse. “If you go to Platres, you feel sorry,” says Yiannakis grimly. “If you go to Prodromos, it doesn’t exist. If you go to Pedoulas, you start crying.”

That’s another issue, and the reason why Yiannakis Papadouris is in the news at the moment: based on his success with Kalopanayiotis, he’s been appointed advisor to the hugely ambitious plan now being formulated by President Anastasiades for saving the 115 communities of the Troodos area. (“I have the right ear of the president,” as he puts it.) Simply put, the government has its work cut out, the decline and depopulation of mountain areas being a decades-old problem. Yiannakis – a man who likes to talk in numbers and concrete examples, as befits a civil engineer – recalls his primary-school days in the 1950s: when he entered school, there were 144 pupils, when he left six years later there were 106. He himself left in his teens, and spent almost 40 years living abroad before coming back and running for community leader.

Why did he do it? There are other examples of local lads turned wealthy benefactors, to be sure – but why him? I wonder if it might’ve been nostalgia, a longing for the half-remembered idyll of his childhood – but in fact he’d already come back for a while in his early 40s, with his now-estranged English wife Kathleen when the girls were small, and it turned out to be a disaster. I wonder if it might’ve been the opposite, a rebellious boy who left on bad terms and wanted to flaunt his success, as if to say ‘I’ll show them’ – but in fact Yiannakis didn’t leave because he was unhappy in Kalopanayiotis, it just happened that way. His older sister (he’s the fourth of five siblings) was a teacher at the Pancyprian Gymnasium and took him with her to Nicosia, then his older brother was in London so, again, he tagged along, drifting into a Civil Engineering degree and later moving to Dubai where he made his fortune.

So why come back? A sense of duty may have been involved; after all, his dad was also community leader, back in the 60s. But an even bigger factor, I suspect, may be simply that Yiannakis thrives on projects and micro-managing. I’m initially a bit embarrassed that he’s giving me such a grand tour of the village; after all, his daughters and their families are here from the UK, waiting for him to have lunch together (he has four grandchildren, two from each daughter; he and his wife aren’t officially divorced, but have “been apart for a very long time”). I soon realise, however, that the tour is as much for his own benefit as it is for mine.

We pause for a beer at the restaurant in Casale Panayiotis, and he calls the waitress over and chides her – gently, but firmly – for not having brought us an ice-cold glass. We go to the spa, which looks homely on the outside but has everything from mud baths and colour therapy to a “snow paradise” on the inside (it cost “about 6.5 million dirh – uh, euros to build,” he tells me, almost saying ‘dirhams’ like they do in Dubai), and he instantly notices that the grass outside the ‘relaxation room’ hasn’t been cut, and makes a call to the person responsible. His style is avuncular, never angry, but he does get involved. A few nights ago he left the estate and stayed in one of the rooms at Casale; “I wanted to see, ‘Am I missing something?’”. Similarly, if a room has some issue that’s supposedly been fixed, he’ll often spend a night there, just to check that it has indeed been fixed.

So he’s very hands-on, it appears.

“I cannot help being a hands-on man!” he laughs. “All my life! Sometimes my fellow employees complained to me that I interfered too much. Thank God now I’m a director, so I say, ‘If a director cannot interfere, who can interfere?’”. The vehicle for his success was Wade Adams, “one of the largest construction companies in the Emirates”, where he rose from site agent to general manager. (Since the move to Kalopanayiotis he’s been kicked upstairs to managing director, still in charge of the company – which he co-owns – without being involved in day-to-day activities.) For years, he worked crazy hours; “I was workaholic all my life,” he confirms. When the company was smaller, he’d work all day then stay on in the evenings preparing tenders for new projects. His girls largely grew up with their mother, he admits, and blames himself for their un-fluent Greek.

Does he wish he’d done things differently?

“Yes and no,” he replies frankly. “I’m – not very good at house chores. I’m not a ‘house-trained person’. So I think it worked for the best.”

One, perhaps unfortunate side effect is a lack of other interests. “I grew up in an age when we didn’t have the comfort to go into sport and hobbies,” says Yiannakis. Even now, his main relaxation is travel (and food and drink, he adds, patting his stomach ruefully); “I travel a hell of a lot”. Even when he travels for pleasure his mind keeps ticking, on the lookout for new ideas. Pots of geraniums line the side of the road at the entrance to Kalopanayiotis; he saw them in Innsbruck, he tells me, and copied the trick in his own village (they’re in bloom all the year round). He likes to move around, dividing his time between here and Dubai, tinkering with his lifestyle as he does with everything else. Despite all the time and effort he’s invested in the village, he admits – and despite how spacious his estate is – he’d go nuts if he had to stay here full-time.

How will such an active, dynamic man cope with working alongside civil servants (not to mention the mukhtars of small mountain villages) on the Troodos plan? It’s a valid question. Yiannakis is private-sector through and through, and scathing when it comes to government departments: “They sit there, they take no initiative, they only do what their bosses instruct them to do… They discover that it’s easier to remain apathetic; the salary’s coming anyway”. A big part of transforming Kalopanayiotis was chasing EU funds to allow the villagers to restore their old homes (not to make them look new, he clarifies, just to give them “the look they used to have”; roof tiles in place of corrugated iron, that kind of thing) – yet he had to employ someone full-time just to run the weekly gauntlet from department to department, or the applications would never have been processed in time. Once, he recalls, he took the initiative to make a development plan for Marathasa, expecting the relevant minister to welcome his ideas; instead, the man raged at him for acting without permission, “and he shouted at every employee who’d helped us. So yes, there is a very big institutional problem”.

How will such an active, dynamic man cope with working alongside civil servants (not to mention the mukhtars of small mountain villages) on the Troodos plan? It’s a valid question. Yiannakis is private-sector through and through, and scathing when it comes to government departments: “They sit there, they take no initiative, they only do what their bosses instruct them to do… They discover that it’s easier to remain apathetic; the salary’s coming anyway”. A big part of transforming Kalopanayiotis was chasing EU funds to allow the villagers to restore their old homes (not to make them look new, he clarifies, just to give them “the look they used to have”; roof tiles in place of corrugated iron, that kind of thing) – yet he had to employ someone full-time just to run the weekly gauntlet from department to department, or the applications would never have been processed in time. Once, he recalls, he took the initiative to make a development plan for Marathasa, expecting the relevant minister to welcome his ideas; instead, the man raged at him for acting without permission, “and he shouted at every employee who’d helped us. So yes, there is a very big institutional problem”.

Things may have changed; certainly, the ministers he’s met so far are a lot more progressive than the one in his story. What about the fear that a government – especially this government – tends to confuse development with developers, though? Is the plan just to build a lot of villas, like in Paphos? “Definitely not,” he says firmly. “Definitely not. If you do that, you’ll kill Troodos forever!”

Legislation needs to change, he explains; different criteria have to apply in the mountains. Cottage industries can’t compete with urban businesses; building regulations need to focus on preserving character, not the building coefficient and “all this bullshit which does not apply to my village”. Unsurprisingly, Yiannakis is taking on the work with a micro-manager’s zeal. He’s hired two people to visit all 115 villages with a detailed 30-page questionnaire, not content just to send it to community leaders. He’s also taken it upon himself to draft a new ‘policy statement’ for rural areas – the current one being unfit for purpose – because “if I leave it to them, it’ll take five or six years and it won’t be a policy statement”. I hope his message gets through, I say earnestly. “It’s getting through,” he reassures me. “But it’s proving more time-consuming, and more expensive, than I thought.”

Looking back, it almost didn’t happen. He was only elected community leader by six votes in 2002 – and of course, had he failed, it’s unlikely he’d have tried again, far more likely he’d have gone back to Dubai and left the village to its decline and decrepitude. Fast-forward 16 years and the place now has christenings and weddings, for the first time in years; “Before, the priest only did funerals!”. We talk pleasantly enough at Yiannakis’ estate, in the shadow of lemon and fig trees – but it’s only when we drive into Kalopanayiotis that I realise how devoted he is to this enterprise, the defining project of his late middle age. See that wall over there? I designed it. See that painting on the wall? It shows what the building was like before we refurbished it. Good morning, Mr. Papadouris. Thank you, Mr. Papadouris.

All in all, Yiannakis Papadouris is good company: down-to-earth, candid, outspoken. Unlike many rich men, he’s neither cagey nor self-important. “I’ve always been a guy who will go less for show, and more for the bricks and mortar,” he says. “Really a civil-engineer approach.” As community leader, he’ll often get phone calls from mayors in Greece or France or Italy, asking for their villages to be twinned; “Come on, it’s a waste of money!” he exclaims to me (I assume he’s more polite to them). Let others worry about cutting ribbons and exchanging plaques, “I am more interested in getting money to restore the roofs, and give a face-lift to all the houses that have not been restored”. He looks around at the steep paths and huddled homes of Kalopanayiotis. His village, in more ways than one.

The post One man and his village appeared first on Cyprus Mail.