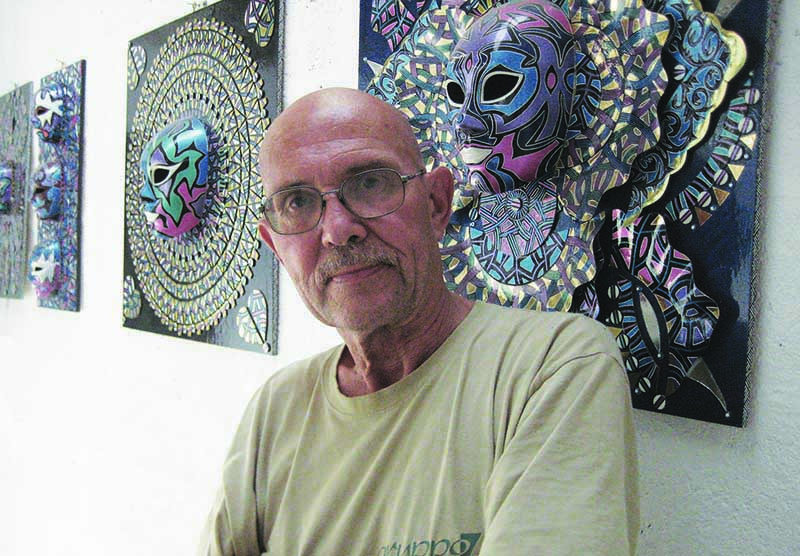

THEO PANAYIDES meets a man much like his art, where little details build a picture of a life that has included being a builder’s labourer and a member of a bikers’ gang

The best way to describe Peter Bird is perhaps to do what he does, i.e. work in miniature. Not that the artworks he produces are small, necessarily. Peter makes so-called ‘visionary art’, sizeable ornamented pieces which take weeks or months to complete – but most of that time is spent hunched over his worktable in the tiny, tiny Larnaca studio that doubles as his living quarters, using “a special curved brush that I cut down myself” to apply acrylic paint in fine, flawless lines, again and again till he gets it right. His paintings contain little panels, each one adorned with little arcs and curlicues of paint. The charm of the whole lies in the details, each one painstakingly honed; it can take an entire day to produce one panel.

The same approach should perhaps be used to describe his 63 years on the planet (so far), the past nine spent in Cyprus, the past seven months spent at Kitium Art Residencies in central Larnaca where he lives and works. It has, after all, been a life of small strokes. He hasn’t – touch wood – had to deal with any major crises or health problems. He’s never married, nor ever been tempted. (“Single guy, single guy!” he avers almost frantically when I broach the subject.) He’s lived – and continues to live – very simply. There’s no grand design to his life; just a steady agglomeration of details, building up (like his paintings) to a singular, highly unusual person.

“You’ll be asking me questions, right?” he double-checks at the start of our interview, clearly unnerved by the thought of having to speak without prompting. (His replies, when I do ask my questions, are as short and precise as his brushstrokes.) We’re on a side street, the silence broken only by the occasional roar of a passing motorcycle. It’s a Saturday afternoon, and very hot. Kitium Art Residencies – four artists’ studios, plus gallery space – is a converted warehouse, its corrugated-iron roof trapping the heat from outside, just as Peter’s own room is a converted storeroom.

His ‘home’ is perhaps four feet by 10 feet, an enclosed wagon-like space with a sofa bed and a handful of furnishings; a small, very steep wooden ladder leads to his studio – “That one’s a bit greasy,” he warns of the top rung, clambering up with practised ease – which is simply the roof of the narrow wagon, piled high with art and looking out over the warehouse. There are, of course, no windows. Isn’t he uncomfortable, living in such a small space? He shrugs: “It doesn’t really bother me”.

His life, you might say, is monastic, devoted to work. He’s dressed in olive pants and matching olive-grey T-shirt, torn at the armpit. “I’m not a big spender, lavish on clothes or anything like that. If I go to get clothes, it’s at a secondhand shop.” He’s gangly and floppy, thin as a rake, with rather odd posture – head hunched forward, arms at his sides – which presumably comes from all those hours huddled over his paintings. He’s shaven-headed, with big round glasses, expressive hand gestures and a slight, intermittent stammer. At first he seems painfully awkward, but in fact he’s quite pleasant, even sociable. It’s a slight surprise to learn that he worked as a builder’s labourer – for 20 years, until his early 40s – and was also part of a biker gang: “Proper bikes, really massive great big ones.” To be fair, they weren’t exactly Hell’s Angels; they just drove around England, 15 or 20 bikers, roaring down the backroads on their weekends and holidays. What was the attraction of motorbikes?

“I don’t know, good question. Just a thing when you’re younger, I suppose. I continued with it, till I got the aches and pains [and] didn’t want to do it anymore, y’know?” The ‘aches and pains’ are mostly arthritis, one reason why he appreciates the warm climate of Cyprus. ‘Good question’, I gradually realise, is his stock response to those questions – usually the more abstract ones – which he isn’t really sure how to answer. Unlike most artists, he’s not too keen on faux-philosophical waffle.

What makes him happy, apart from work?

“That’s a good question. Happy…” muses Peter, as if handling a nugget of kryptonite – then prefers to evade it altogether. “Maybe happy doing my work. You know? Even if you don’t sell work, something still drives you to create work all the time. Doesn’t make me off-put if I don’t sell any work, I’d still create work… So yeah, happy.”

Being happy, I suspect, isn’t something he thinks about; he just is, or he isn’t (and usually is). He left school at 15, with no qualifications – and the first job he found was as a gravedigger, which he did for two years. Rather a depressing job for a 15-year-old, surely? “You got used to it,” he shrugs, with the air of waving off a minor irrelevance, adding proudly that “it’s all done by hand”, or it was in those days; “Pickaxe, shovel, and you dug [the grave] by hand”. From there he went to a timber yard, stacking timber for a further three years – then came his time in the builder’s trade, which was both enjoyable and lucrative.

“I was on the price gang, I was earning £500 a week,” recalls Peter. “It’s called a price gang, and it’s literally running around – because the bricklayer gets paid for how many bricks he lays, so if the bricklayer’s going fast, the labourer’s got to go fast. I was running up and down ladders, running up and sliding down them all the time, all day. I was quite fit when I was younger”.

He’s always liked manual work – even now (or especially now), as an artist and craftsman. It’s a bit surprising that his education ended at 15, since the family weren’t poor; his dad was a civil servant doing something hush-hush (“He’d signed the Official Secrets Act, he was somewhere up in the mysterious places… He was an engineer, as far as I know”), not exactly the typical background for a teenage gravedigger and timber-stacker – but the boy simply wasn’t academic. “In them days, I didn’t really want to take any exams. I just wanted to leave school”. He was sporty, and a keen freshwater fisherman. He wasn’t – and still isn’t – much of a reader. Yet he’d always do some drawing on the side, keeping it a secret from his biker friends and fellow labourers – not because they’d laugh, they just wouldn’t be interested. He honed his skills copying album covers (not just tracing but copying by hand, in black and white) then, as he grew older, became more professional. “I was doing workshops, and having exhibitions here and there.”

All the little details, building up a picture of a very particular person. A physical – as opposed to cerebral – person, digging graves and sliding down ladders, butterfly-hunting as a boy in his grandpa’s allotment. A risk-averse person, having “pondered on the idea” for a whole year before taking the decision to move to Cyprus (his older brother lived here at the time, and told him of a job looking after student accommodation at the Cyprus College of Art, later the Cornaro Institute). A quiet person, musing that he’d like to buy a place “out of the hustle and bustle” if he won the lottery (does a side street in Larnaca really count as hustle and bustle?). An austere, quite ascetic person, who seldom drinks and has no interest in food; his only vices, he says, are coffee and cigarettes, which are what gets him through the day in that cramped little studio. Also, it seems, quite a private – or just free-spirited – person. Does he miss anything about England?

“England? Not much at the moment with what’s going on there, all the rules and regulations and stuff. You know? And people watching you”.

Rules about what?

“Everything, isn’t it? Everyone’s spying on you, aren’t they? – looking at what you do. If you put the dustbin out, you’ve got to keep it level… You have spies looking, round the corner”. Meaning neighbours? “Yeah. Or in the council, things like that.”

It all comes together in his life (and art) at the Kitium Art Residencies – a gloriously private life where few people even see him, let alone tell him what to do; an austere life, neither spacious nor especially comfortable but devoted to his work, like some mediaeval monk; a quiet life and a physical one, working with his hands all day. He takes care of the studio (which fetches a small monthly wage) and will also – unlike a mediaeval monk – teach the occasional workshop. ‘Quiet’ shouldn’t be confused with ‘misanthropic’: Peter has friends, and will often walk downtown for a chat or a bite to eat. He’s happy to talk if people “drift past” the studio, which they often do. Don’t forget he got along with builders and bikers for years – though it may be significant that he’s long since lost touch with his old biker pals, and has only been back in England once in the nine years since he left. He’s not, it seems, a very sentimental person.

It all comes together in his life (and art) at the Kitium Art Residencies – a gloriously private life where few people even see him, let alone tell him what to do; an austere life, neither spacious nor especially comfortable but devoted to his work, like some mediaeval monk; a quiet life and a physical one, working with his hands all day. He takes care of the studio (which fetches a small monthly wage) and will also – unlike a mediaeval monk – teach the occasional workshop. ‘Quiet’ shouldn’t be confused with ‘misanthropic’: Peter has friends, and will often walk downtown for a chat or a bite to eat. He’s happy to talk if people “drift past” the studio, which they often do. Don’t forget he got along with builders and bikers for years – though it may be significant that he’s long since lost touch with his old biker pals, and has only been back in England once in the nine years since he left. He’s not, it seems, a very sentimental person.

His art isn’t really sentimental, either; it’s precise, influenced by a life-changing trip to Luxor where he marvelled at the ancient Egyptians’ architectural feats (“You can’t get a razor blade in between the joins, they’re that perfect”) and determined to bring that same accuracy to his own “line”. His art, like his life, is conducted on a low budget: almost all his materials are found objects, “discarded things” – shower heads, feathers, shells, light fittings, sequins, little stones, old CDs, a chain from a sink plug, a chipboard table he found in a skip – the main exception being the plastic masks in the centre of his compositions (which he either buys, or makes on a mould). His art, like his life, is single-minded; he takes his time, and won’t be distracted. “If I make a mistake, I put black over it, and start again,” explains Peter. One particular piece took an astonishing six months to finish.

The days fly by easily enough: up at six, coffee and a croissant, then paint for a few hours, quick break for coffee and a cigarette, back to painting, half-hour break for lunch, back in the studio till mid-afternoon, then he’ll do a few chores and maybe paint again in the evening, if he’s not going out. Now and then – once every three weeks, say – he’ll go scavenging for materials, checking out skips and secondhand shops. He lives on his meagre caretaker’s salary, and what’s left of his savings; for some reason – maybe because he’s not too handy with computers – he doesn’t really market his work, and has barely sold (or attempted to sell) anything since coming to Cyprus. Still, he’s not fussed. He’ll be 65 in two years, hence eligible for a pension – and he’s happy to keep living this life, as long as “my hands are good” and the work isn’t sub-standard.

What kind of person are we talking about here? Not, he insists, a spiritual person – “Not at all” – yet he’ll often “enter a different reality” when engrossed in his work. His art draws from all kinds of cultures (Indian, Egyptian, Celtic) and he’ll actually see these ancient people, very clearly, in his head, imagining their lives in a kind of vivid dream while assembling shower heads and sequins and CDs, or applying paint with his special curved brush. When he worked at Cornaro he was also in charge of the art shop, and had to keep pausing to hand out supplies to students – but “I’d just stop, serve, get back to my mindset, continue”. In the end, Peter’s greatest trait is perhaps his ability to focus so completely, on the life he’s chosen and the work that makes it worthwhile.

What would he do, if he couldn’t create?

“That’s a good question.” A pause. “I don’t know. This is all I know, I can’t really answer that… ’Cause when I’m doing my work, you get into a self-meditation state. You know, background doesn’t exist. You lose track of time. People walk in, [but] you’ve got no sense of anyone there”. Peter nods: “Yes, it’s very therapeutic, my kind of work”. A glimmer of some larger meaning, side-by-side with the miniature details. I leave him, a thin gangly figure in olive, and return to the muggy heat of the outside world.

The post Larnaca artist values craft over comfort appeared first on Cyprus Mail.